Issue Number 25, Summer 2014

Contents

- The Ancestors by Michael Hettich

- "If You’re Reading This, You Might Be a Baboon"

by Susan Cohen - A Chechen poet writes

How does the world forget us/Suffer our massacre /with such indifference? by Karin Spitfire - Affordable Flowers by Leonore Wilson

- Ardea Alba by Richard Jordan

- City Underwater by Sebastian Paramo

- Coal Train by Carl Stilwell

- If a Blackbird by Margot Farrington

- If I can be in my bones, I will be truthful by Lauren Lockhart

- Last Bird by Joe Paddock

- Leaf Glossolalia by Sally Molini

- Letters from the Hinterland #9, Consumption by Raymond Greiner

- Loafing by Barbara Crooker

- Looking Back From an Undisclosed Location by Mike Pulley

- Paperless...Jobless by Catherine Evleshin

- Streaked-Winged Red Skimmer by Diana Woodcock

- The Horizon Empties by David Faldet

- The Lake, the Quiet by Linda Benninghoff

- The Rate of Disappearance by Hadley Hury

- Yangshuo, China: Watching a Fisherman's Cormorant on the Li River by Dave Evans

Archives: by Issue | by Author Name

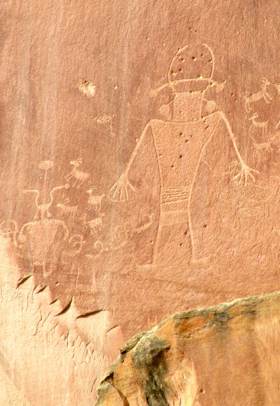

The Ancestors

by Michael Hettich

Michael lives on the Atlantic Coastal Ridge in the Biscayne Bay Watershed of South Florida, a mile west of Biscayne Bay.

The ancestors watch us from behind the scree

and trifles of our lives. You think you’re alone

in your moment? they ask—the way a leaf shivers

without breeze, or a breath is inhaled

where there is no body. We call that the wind.

But the ancestors watch us like the dark beyond daylight

makes the wild animals move through the trees

until we can’t see them. Until they have no names.

You might call them birds, but the ancestors are never birds.

Maybe stones or grasses. Wildflowers. Forgotten words.

Now someone says softly the wild birds are going

extinct, the warblers and thrushes that migrate

thousands of miles. Or the way summer fragrance

covers the scent of things falling back to earth

as the ancestors did, long ago, living here

although we refuse to acknowledge them, pretending

our muscles and minds and hearts are our own

and everything lives only now.

Previously appeared in The White Pelican Review

© Michael Hettich

"If You’re Reading This, You Might Be a Baboon"

Headline in the Christian Science Monitor when scientists discovered baboons could be taught to recognize which letter patterns make words and which are gibberish.

by Susan Cohen

Susan spends much of her time looking for birds in both the San Pablo Bay and the Bodega Bay watersheds of Northern California.

And you might be bristling as you read

the planet’s news after a rough night

in the Jackalberry tree,

when all you ever wanted

was your morning cuppa

and the harmless flesh

of roots, juicy fruit of baobab

before commencing your commute

across the savannah.

You might be studying the encyclopedia

of a waterhole, spelling out b-a-d weather

from the sky’s alphabet.

You might be reading up on humans

in the newly torn pages

of ancient jungles:

the hard truths of our macadam,

the visible clouds we belch

from our metallic shells,

our tracks that flatten grass,

the signs we post and mock

with bullet holes.

You might be trying to read your future,

puzzling over words

with silent endings.

© Susan Cohen

A Chechen poet writes

How does the world forget us/Suffer our massacre /with such indifference?

by Karin Spitfire

Karin has lived at the tidal mouth of the Passagassawakaeg River and W. Penobscot Bay for 27 years, just above where the sardine factory operated until 2001.

Chechnya, Bosnia, Rwanda,

Somalia, Darfur

just the names

recoil off my eardrums

a finger touching a hot stove

Three days after cancer killed my brother

my nephew got his own malignancy markers

Earlier that summer, the men discussed

their yearly application of chem-lawn

and were happy with less clover, fewer bees

Can I say one shock

blocks another, the next

A slew of us

still in reaction to Columbus, slavery

Dachau, the mess of every veteran’s battle,

or a very specific domestic war

on children, women and crabgrass

I plead guilty

Can I say I am safe and I like it

that I had the same poet’s question

in my father’s house at seven

and I have learned not to hear

that cry coming from every third

door in my neighborhood

never mind across the continents

I lived, I got out

circumvented the myriad missteps available

didn’t get caught in the sex-traffic route waiting for me

Can I say I am struggling in my limbic system

for a ceasefire

slow-going, meticulous work

making a biodynamic farm

from the rubble

or at least something

that yields

more rows of repetitive movements of peace

more cross-pollinating compassion

than harm to self or others

something possibly as relentless as

each year’s upturned crop of rocks

I lived: so I compost

Can I say I don’t think it is enough

But I work to keep myself from

going down the redundant paths

of finger-pointing, they-saying,

bursts of fury

I feed the truce

I work to keep myself from yapping

without a lick of action,

grief pooling

into cement of despair,

I wrack the pleura free

I weep to keep my heart open

Can I be unarmed

in the wide-open next step

Hear the underlying drone of love

while the bees are disappearing?

© Karin Spitfire

Affordable Flowers

by Leonore Wilson

Leonore lives in the Capell Valley Watershed on a 1200-acre holistic cattle ranch that has been in her family since 1915. Her concern is saving it from "water nabbers," those who want to bulldoze the land for vineyards.

If only love were acquired easily as these:

The self-assured white roses, edifice of lilies,

Bleeding narcissus and rosemary, the awe

Of halved-milk cartons wielding the bunches

Of glib petals on a country road in August.

But no, remember Swann wrapped up in his illusions:

The little violin sonata by Franck

Replaying in his head, giving him grief

And happiness; the heavy syllables that soured

In his belly when he spoke her name, Odette.

Love with all its clumsiness, confusions,

Consequences. The law of the dragonfly

Battering his wings over the tar pit until he sticks.

That type of habit we’re enchanted by:

Dumb pomp and ardent spark of hurt.

Now they’re selling chrysanthemums and orange nasturtiums

On weekends in that light blue enameled booth

Under the oaks and palpitations of October.

So few gravitate to purchase. The prudent children

Wait who have picked the admirable from the grandfatherly shadows.

No one stops. The good society perhaps is inured now

To beauty. No one plays music in the garden anymore.

No one is seduced by the tea-colored pond or the illumination of ponies.

The faithful go home to their faithful grey flats, their private rooms.

The flowers remain harmonious, brilliant, undefeated.

© Leonore Wilson

Ardea Alba

by Richard Jordan

Richard lives in the Nashoba Valley in Eastern Massachusetts not far from the Nashua and Squannacook Rivers

Below the factory

that used to make

the river bleed

indigo and sienna,

I crouched beside

a wooden bridge

in morning light

to watch an egret

work the reeds.

Sleek & blinding

white, a specter

I believed come back

to show me something,

she took a cautious step,

froze then slowly stretched

her neck. A pickup, passing,

shook the bridge, jarred

me away & when I looked

again, she'd already spread her wings,

a sunfish sliding down her slender beak.

© Richard Jordan

City Underwater

by Sebastian Paramo

Sebastian currently lives in Harlem, which lies in the Lower Hudson Watershed. This puts him within short walking distance to the Harlem River, the name for the body of water that connects the Hudson and East Rivers.

Several feet below the surface, the ocean looks like a sky.

There's so much blue, it makes us blind. We go blind for

the surface so opaque it feels like an older time.

There is not one happy bone left, only the blur of sunlight.

We think of ways to reach the surface.

Ways to break the blue glass, to surface without thought,

surprise or fear. That world is like heaven to us.

We've been in the dark too long.

© Sebastian Paramo

Coal Train

by Carl Stilwell

Now living in Pasadena, Carl's true and long-time home was in South Pasadena, a block away from a concrete-paved river called Arroyo Seco, which was called by the Tongva, its first people, Hahamongna, "water flowing through fruitful valley."

Coal trains earthquake our home every night around one-thirty. Eighteen-wheel trucks rumble 24/7 on nearby mountain roads. We worry that the upstream impoundment will break and drown us in coal slurry.

Explosives the size of the Hiroshima bomb drop on Appalachia every week. Mountaintop removal has destroyed 500 mountains.

Coal trains earthquake our home every night around one-thirty. Eighteen-wheel trucks rumble 24/7 on nearby mountain roads. We worry that the upstream impoundment will break and drown us in coal slurry.

Explosives the size of the Hiroshima bomb drop on Appalachia every week. Mountaintop removal has destroyed 500 mountains, buried 2,000 miles of Appalachian streams beneath toxic debris. Six of my neighbors have brain tumors.

Almost one third of America’s coal is from Appalachia. Nearly half of the nation’s electricity comes from burning this fossil fuel. So coal trains earthquake our home every night around one-thirty.

Coal emissions are the largest contributor of carbon dioxide increases in the sky. Another Greenland glacier melts and falls into the sea. We worry that the upstream impoundment will break and drown us in coal slurry.

Massey Coal has 60,000 violations, but nobody in government will stop them. Is this the best way we can turn on the switch? Coal trains earthquake our home every night around one-thirty. We worry that the upstream impoundment will break, drown us in coal slurry.

Fly ash spills have contaminated our soil and our water. Six of my neighbors have brain tumors.

Almost one third of America’s coal is from Appalachia. Nearly half of the nation’s electricity comes from burning this fossil fuel. So coal trains earthquake our home every night around one-thirty.

Coal emissions are the largest contributor of carbon dioxide increases in the sky. Another Greenland glacier melts and falls into the sea. We worry that the upstream impoundment will break and drown us in coal slurry.

Massey Coal has 60,000 violations, but nobody in government will stop them. Is this the best way we can turn on the switch? Coal trains earthquake our home every night around one-thirty. We worry that the upstream impoundment will break, drown us in coal slurry.

© Carl Stilwell

If a Blackbird

by Margot Farrington

Margot lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, two blocks from the tidal sweep of the East River--a major flyway for migratory birds.

If a blackbird--wing’s flare-red and

cream-crescent out of sight,

his streaky mate tucked

in long grasses--

if a blackbird, his oak-a-lee

contained in his whistle-box,

bends stem after stem to bring down

moons of phantom, waning dandelions

if a blackbird---help me, please,

I am repetition and so is he--

if a blackbird ducks his pure night head

in early morning sun

down to a foot, also dark,

to eat the spread of starry seeds

to feast on the bounty of this day,

may we take it as a sign

to make him magician of every appearance

miraculous and simple?

He conjures this arch of blue held

by keystone of birdsong,

the separate, shining welcome

from each leaf, each blade of grass.

Through him we inhale lilac,

exhale hayfield, as he pulls

handkerchief memories

bright-lined through our minds.

From his epaulet, tiny strawberries

fall to our tranced fingers,

that in the grotto of our mouths we may

taste what is wildest.

And to us he transfers his heat:

sweet coal of summer sun, that our

touch might ignite each other to flames

upon the cool bed.

For he commands our amazing hands,

and all they may do this day.

And if a blackbird, at day's end,

returns to the round of the

new nest, open as a mouth

at the wonders of the world--

if a blackbird, who knows nothing

of what we are forced to know,

swallows only the precious moments

starry and single - purposed as seeds and

converts them by way of his song

to paradise as he knows it,

what should we do but follow him?

When he folds his wings upon the flight

Da Vinci once dreamed, he sways on a reed,

tuning himself in the hush. A breeze

unfolds; he dips and rows with a few notes

liquidly towards twilight.

O, let us have whatever of him

we can possibly manage, let us strive

to loosen our complexities, come

to a place still and serene--

keeping as best we can

within the little clearing of now.

Previously published in the author's book Scanning For Tigers (Free Scholar Press, 2014)

© Margot Farrington

If I can be in my bones, I will be truthful

by Lauren Lockhart

Lauren lives on the eastern side of the Colorado Rocky Mountains in the South Platte River watershed.

Aqueous quiet throbs

like a separate arrangement of veins

turning soundless bright nothing

in coated circles under

a cloak of cells. The atoms

of my blood aren't

mine

I am borrowing this molecular tangle

from the forest

from the moss

from the tributaries and

I am reminded of this:

our vascular order learned how to branch

from the river

and from the black arms of the winter

walnut tree

that fingers a blank sky

in the glinting Indiana dusk.

© Lauren Lockhart

Last Bird

by Joe Paddock

Joe lives on the easy green contours of the Crow River watershed, a landscape sculpted by myriad capillaries of flowing water--great art if ever there was.

(Earth is currently losing something on the order of 30,000 species per year — some three species per hour.)

Maybe 15 years ago,

blurry now in memory, the story

on public radio in Hawaii,

how a last bird of its kind--I can't

remember its name--

had been discovered, and

the reporter and guide

were listening to, recording,

its song. I do remember clearly

the full richness of its warble,

somehow tired and forlorn, a song

that continues in me, sounding

down through the years,

only in me: the bird, the last

of its species, a male, lost

in the hormonal fires

of his breeding season, lonely,

singing to call in a mate, one

that didn’t exist, that wasn’t.

He sang and he sang, and cruel,

the reporter and biologist

played for the longing bird

a recording, an echo

from out of the past,

of a full-throated female response.

Oh then how the male bird burst

into glorious song!

Previously published in the author's book Dark Dreaming, Global Dimming (Red Dragonfly Press, 2009)

© Joe Paddock

Leaf Glossolalia

by Sally Molini

Sally lives and writes near Heron Haven, a spring-fed wetlands sanctuary and one of the last ox-bow wetlands of Big Papillion Creek.

I've listened and taken

notes, the rustle and hiss

can't be nonsense,

so many tongues for anyone

to hear -- pinnate, whorled, elliptic,

lobed, their meaning lost

on humans. Birds could translate

but don't have time for all the trees

whispering their summer

plans and heartwood stories,

lamina-lisped dialects

of maple, willow and ash,

dry sighs from a birch copse,

the linden's slow foliole

phasia, scots pine forest

a blue-green buzz of reach

and light as each root

hurries to reap what's left.

Previously published in Tar River Poetry, Spring 2008

© Sally Molini

Letters from the Hinterland #9, Consumption

by Raymond Greiner

Raymond lives with his canine companions Orion and Venus on 14 acres of remote forested and pasture land about three miles from the hamlet of Paragon, Indiana, in a cabin about 500 yards from the little-traveled road.

When I was a kid during the 1950s our town had many stores, mostly family owned and operated, and these stores were designed to fulfill particular consumer needs. Clothing stores, supermarkets, and sporting goods stores were all individually owned. Gas stations too were locally owned, with vehicle service equal in importance to selling gas. Department stores were only found in larger cities, and it was a special event to travel to Columbus and ride the escalators at the Lazarus department store. I lived in a smaller town, Marion, Ohio, about 40 miles north of Columbus. We dressed in our Sunday best for these excursions. The Midwest, during that era, was a fascinating place to experience youth.

In this modern era things have evolved into quite a different shopping climate. We no longer have stores, we have institutions with acre-size buildings, which house every imaginable consumer item in organized rows with signage to direct customers, and phones located at strategic locations to call for assistance to locate a particular item. A fleet of electric, riding-shopping carts is available for those unable or unwilling to combine a day hike with their shopping experience

Consumption is an interesting word. It covers a broad spectrum of pursuits. Even when we breathe we consume air, which is a necessity for life. We also will die without water and food. These are necessary consumptions.

Questions arise regarding consumption of other commodities than those necessary for life. Consumption conflicts arise over the elusive line of distinction between real needs and unnecessary wants. We are surrounded by influences, directly and indirectly. The purveyors of consumer commodities design and calculate like mad scientists to influence consumers to purchase more and more, creating markets that reach far beyond basic needs and have caused present-day consumption to grow into a monstrous entity. In H. G. Wells’ (1895) novel, The Time Machine, a scientist invents a time machine and ultimately becomes a time traveler, landing in the year 800,701 AD far far into the future and discovering a beautiful but mindless race of people called the Eloi. This race spends their days in leisure idleness, and his first experience with them is seeing a woman drowning in a nearby river, struggling for her life, as her fellow Eloi lounge on the riverbank and pay no attention to her plight. The traveler is in disbelief and saves the woman himself. As the story unfolds it is disclosed that the Eloi are under the control of another race, the Morlocks, troll-like beings who live underground in caves. At intervals a siren sounds and the Eloi become immediately entranced. They walk in a semi-conscious state toward the sound of the siren and enter the Morlock’s cave to be eaten by the Morlocks. The Eloi are like cattle, harvested by the Morlocks at their convenience.

I see a similarity to this story unfolding in today’s over consumptive culture, which is greatly influenced by the sirens of clever and manipulative marketing techniques. Product choice and availability have grown exponentially, adding dimension and confusion simultaneously. The human mind can be twisted and manipulated quite easily, it seems. We can become entranced like the Eloi, falling victim to wants injected into our veins by astute, psychologically implanted marketing. The difference is the modern day Morlocks are fleecing us instead of eating us.

Another arena of dubious consumption is the food we eat. Foods are purposely enhanced through clever processing designed to cause addictive cravings that have nothing to do with nutritional needs. Modern-day, highly-processed foods are largely aimed at satisfying emotional cravings for certain foods and additives. The Morlock marketers know exactly how to increase food consumption, and it is working well. The obesity epidemic is an obvious result.

The same technique is used in marketing the wonders of technology. The device you have in your hand was outdated at the time of purchase. The high tech folks have new, updated versions waiting in the wings, as they allow the old ideas time for market marinating, establishing a place, before they bring on the next-generation device and the consumer is tempted (required?) to upgrade. It’s the Morlock siren of manipulation using a market desire created to be fueled by peer pressures and the sheep mentality that has crept into present day culture. “Got to have one of those!”

So, what do we do? I suppose we must evolve as we have historically. We must become more individualistic, much like our ancestors and previous generations. Knowledge of exactly what is happening is a good place to start. Discover individual patterns of consumption that counter the Morlock marketers. Options do exist, good options, if we take time and thought to seek them out. Food consumption is an excellent place to begin the change. Locally grown fresh, whole foods are still available. Think through decisions regarding gadgets and devices, evaluate real needs over spontaneous responses to every new twist and turn that technology offers. High-end technology is now ingrained in our culture, and it is here to stay. It’s all about change, adaptation and mindfulness. It can be done.

© Raymond Greiner

Loafing

by Barbara Crooker

Barbara lives near the Little Jordan, a branch of the Jordan Creek, part of the Lehigh Watershed in rural northeastern Pennsylvania.

All right, I’ll admit it, I have just spent the afternoon

watching a street gang of mockingbirds chase each other

in and out of the redbud tree, the walnut,

and all the low lying hedges, the winner challenging

the losers to an acapella sing-off, a braggadocio mix

of cardinal, chickadee, rusty gate, old muffler,

far-off train. They fly low, modified dragsters;

you can almost see the flames stenciled on their sides.

The subtext is me! me! All about me! In the bushes,

the girls are unimpressed. They yawn, flick

their gray and white fans, and are gone.

© Barbara Crooker

Looking Back From an Undisclosed Location

by Mike Pulley

Mike lives near the boundary between the Seneca and Saluda watersheds in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Upstate South Carolina. He has observed nearly 30 species of birds living on or passing through his half-acre home-lot. In addition, there are occasional visits from groundhogs, chipmunks, rabbits, frogs, squirrels, and black snakes.

It was a worn-out empire,

Old in its slums, ruts, and infrastructure,

The collapse of bridges nearly a daily occurrence.

Most disturbing, the loss of songbirds and frogs,

A perdition that broke the spirit of the people

Surely as hordes eating the enemy’s young.

Starvation set in with the death of the bees.

Nightmare segments on the developing world

Something to avoid for sanity,

The lost species count, too, for that matter.

I left the flatulence and paranoia of the South

And hitched a ride West across an arid plain

To a place to be alone and in love

With my own indulgences,

A place to be a relaxing artist

And die like an animal abandoned on a tarmac

Of potholes. Some nights

I woke up late and peered out

My apartment window

To catch a pair of rabbits in frivolity,

In teasing movements associated with smiling dogs.

It was a time of new parables and alchemist formulas

Embedded in paperbacks sold in drugstore magazine racks,

The time when young, mannish women performed music

Of primitive elegance in the remaining venues.

The Devil was apparent

In the spiels of desperate car dealers.

They sold obsolete vehicles for tickets to Vegas

Where they gorged on the last female legs.

They were determined to die

Like shrink-wrap in landfills.

Ultimately, the guns got the best of them

And it was up to grievous angels to intercede

And speak the language of old washing machines,

Talk of water as pure as protected maidens in spring dresses.

© Mike Pulley

Paperless...Jobless

by Catherine Evleshin

Catherine lives at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, in the greenest city in the nation, with views of Mount St. Helens and Mount Hood when water is not falling from the skies.

The package should have arrived days ago. I watch two squirrels race up the cedar tree and out onto a branch that overhangs the deck of my cabin. My cell phone rings and my neighbor's number appears on the screen. Before greetings, I blurt out, "Did you get a package addressed to me?" Too quick.

"No, that cute postman delivered zero, zilch, nada. It's been five days now. Sounds like you're expecting something important."

"...No-o." Not quick enough. The male squirrel rises on his hind legs and watches me with unblinking eyes.

"I'm going over to bring Myra her mail. The postman was the highlight of her day. I'll stop by your place on my way home." With deliveries sporadic, the responsible residents of Greenwood Hills have convinced the postmistress to release the mail to them as a community duty to help out neighbors in isolated cottages. Since my car stopped running, Myra arrives from time to time, bag of croissants in hand, for an update on the roving raccoons, and an examination of spring plantings.

The postal rebellion began last year, when a referendum prohibiting junk mail appeared on the state ballot. The measure would have been a landslide, but corporations screamed First Amendment rights and called for an injunction. After the Internet became the preferred means of communication, bulk mail had kept their workers employed for years, so the USPS sided with private enterprise.

From coast to coast, greenies sprang into insurrection mode. I joined the army of committed environmentalists, and stuffed solicitations, addresses blacked out, into the drop box in town. The police had more pressing matters than to stake out litterbugs.

A breeze purrs through the grove of tall pines to the north of my property. For two years, I have managed to steer the garden tours away from my cash crop of cannabis planted on the steep, unbuildable land behind my property line. Logged over, the acreage has been abandoned to crooked saplings, rotting stumps, and poison oak.

I plan each year to beautify it with two dozen bright green bushes that will keep me above water until I am old enough to collect my pension. A successful crop may enable me to get my car fixed. In the anemic economy, property sales will never again reach their millennial frenzy, and no one hires a middle-aged woman whose skills are limited to filling out title transfer forms for an escrow company.

On nights when the moon turns the ravaged forest into a mystic landscape, I drag four long, connected hoses up the hill, and irrigate my clandestine garden. In front of the cabin facing the county road, I drench the flower and vegetable plots with wasteful spiraling sprinklers and jetting rain birds, to avert suspicion from my excessive summer water bills.

This first descent into felony began two years ago, when my unemployment checks ran out. I drove to San Francisco to learn about hemp production as an alternative to killing trees for paper. The US government prohibits even marijuana's poor cousin with its minuscule percentage of THC, but several states have defied the ban. The DEA can't keep up with high-grade marijuana production, let alone the fields of fibrous and non-hallucinogenic cannabis, used for millennia across the world, in the production of textiles, rope, and, yes, paper.

I should not have listened to the manager of a bustling shop that dispensed medical marijuana. When I mentioned my limited resources, he said, "To turn a profit, hemp production requires experience and equipment -- a big operation. Let me suggest another idea to you."

I now suspect he had apprenticed with Monsanto, the multinational corporation that sells African farmers seeds producing sterile plants. He persuaded me to purchase an engineered variety with high THC content, and hooked me up with a trustworthy retailer in my area. He dug in a drawer and held up a clear plastic zip bag filled with seeds. "Best herb grown outside of Canada. Guaranteed to get you five hundred dollars a pound." With medical marijuana dispensaries springing up like weeds across the nation, but the dealer assured me that any day now, the state would legalize marijuana altogether.

Genetically modified cannabis is prohibited for medical use, but last year my yield exceeded expectations. However, in the cover of night, harvesting the tough plants wrecked my lower back and sent me to the clinic with a maddening poison oak rash. Undaunted, I ordered more seeds through the faltering postal system, addressed to the mailbox that now stands empty at the end of my driveway.

If luck is with me, the man in San Francisco kept my money and his seeds. I'm too old to survive prison.

I leave the squirrels to refill my coffee cup. Returning to the deck, I power up my old e-reader with its dull grey background. I miss the feel of paper, and the ease of referring back and forth through the pages of a print book. I start the latest bestseller on climate change, but doomsday stats in the introductory chapter fail to distract me from the missing package. It will sit in the local post office until someone grows curious.

My cell phone rings again-- my sister on the opposite coast -- with her six-figure income and the conviction that voting will achieve social change. She would consider my entrepreneurial venture a bad joke, so I have told her that I live off investments. She asks, "Did you get any mail this week?"

Neither have I confessed to her my participation in the junk mail coup d'état. "Not for five days."

"They're telling us to check online for anything important, then go down and pick it up." My sister places convention and convenience first, environment be damned. I have failed to convince her that I would appreciate an online singing birthday card as much as one with gilded roses on heavy paper, delivered through the postal service.

When I try to interest her in the new climate change report, she asks, "Have you checked out the new e-readers?" Count on my sister to purchase the latest extravagance with leather bindings and fifty real e-printed pages that turn like leaves in a book.

"How long does it take for the next fifty pages to appear?"

"The device senses when you reach the last page, and downloads the next installment in seconds. You can mark the margins with the stylus provided, and access references anytime."

I imagine plastic and sweating hands." Do the pages feel like real paper?"

"You can't tell the difference. For diehards, there's a musty smell option." Self-assured chuckle. "So, sister dear, you can no longer accuse me of forest genocide. Uh-oh, got another call."

The over-priced widget would curtail my urge to peek at plot endings. I'll drop hints for Christmas. Perhaps they allow e-readers in jail.

A pickup truck slows by the mailbox and turns into my driveway, scattering the squirrels to higher branches. Muscular legs descend from the cab, and I recognize the postman, not in his USPS-issue short pants, but wearing jeans and a tee shirt with "OCCUPY" printed above a row of upraised white, black, and brown fists. I had never noticed the two lines etched between his eyebrows. "I got laid off."

"Sorry to hear that." Awkward silence. His outfit looks like it came from the wardrobe department of a crime show I saw last week about undercover DEA agents.

"Do you need any yard work done, Ms. Wilding?"

This time, I pace my reply. "I do it myself.” I shift in my deck chair, exciting the pain in my back. “Keeps me in shape."

He stares into the branches of the untrimmed cedar tree. "Remember me if you need any heavy work or hauling." Forlorn smile belying a narc, he offers a photo-shopped business card printed on cheap stock. A sting of guilt for stuffing the junk mail into the drop box.

He starts toward his truck, stops, and turns back to me. "Say, a package for you has been sitting in the post office for days. Have they called you about it?"

Sweat trickles down my sides while I envision pale sprouts inching through brown paper wrapping. "My car's not running. You couldn't by any chance bring it to me? I'll pay you."

"Be glad to. Do you need anything from the supermarket while I'm in town?" A cop would never think of that.

"It's a deal." I collect my grocery list from the kitchen. The resourceful young man looks it over and takes the cash from my hand. I tell him, "Myra Walker needs some work done. I'll call and let her know you might stop by."

His grateful sigh puts to rest my remaining doubts about the postman. The roar of his pickup truck fades down the county road, and I inhale the scent of cedar. The wind rattles the pines and the male squirrel makes that clicking noise in his throat.

Previously published in words apart magazine

© Catherine Evleshin

Streaked-Winged Red Skimmer

by Diana Woodcock

Diana lives on the Qatari Peninsula, which lies on the northeasterly coast of the much grander Arabian Peninsula, surrounded on three sides by the Arabian (Persian) Gulf— poised perfectly between sea and desert.

One dragonfly lingers

on the brown tip of a summer

green reed like a flame

on a candle at mass.

Poison has spoiled its meal

of midges and broken its eggs.

The last of its kind

to inhabit this shoreline,

it hangs on,

burns in the mid-day sun,

purifying the day.

No longer skimming

its lake, it poses on its reedy

throne—a lone ember

glowing in the fumes

of Malathion.

Previously published in Least-loved Beasts of the Really Wild West, Native West Press (anthology, Spring 1997); Creekwalker, Summer 2007; Swaying on the Elephant’s Shoulders (Little Red Tree Publishing, 2010)

© Diana Woodcock

The Horizon Empties

by David Faldet

David lives on Dry Run, a tributary of the Upper Iowa River.

How patiently, climbing down from trees,

we unstooped, lengthening our stride. How high,

and over what length, leveled our gaze to see

what moved. We stepped from shade to blistering

sun and relished it, knowing eland, hare

and waterbuck in their cocoons of fur

would hesitate to flush beneath its glare

and tire early, panting. With each repeat

their blurry sprint, their pounding blast,

diminished, until we faced them:

panting, tongues out, in range at last

of the rocks we carried. We waded singing

into the grass our grandparents dreaded.

The blood it gave up was not our own

but that of quick beasts who could not shed

their skins without our help. Sweating, at a trot

we sought them beneath the white sky.

At dusk, their meat sizzled on our fires.

Their nostrils quivered as they tried

to scent the odor that poured in streams

from naked skin the sun, our god, burned black.

We scorched the plains around us. We thinned

the charging herds of horned buffalo, of racked

impala bulls. At dark we wrapped their hides

around us. At light we bared ourselves again

and ran one river to the next, crossed naked

crests into new country. Once again we won

the forests – this time keeping to the earth –

and burned them. The overheated mastodon,

the sloth, the shadowing clouds of pigeons

we erased. Wolf, bear, cougar, lynx are gone

from the hills we claimed. Their fat

fed our flames. The sun, growing hotter,

honors us. The horizon empties at its touch.

© David Faldet

The Lake, the Quiet

by Linda Benninghoff

Linda lives in the Northern Long Island Watershed in back of Caumsett State Park and less than a mile from the Long Island Sound.

The lake, the quiet

the kneeling sofa and chairs,

then my dog barking at planes,

and the patriotic fireworks.

I find myself in simple things,

pouring you tea

when you have injured your back,

the weight of groceries in the bag,

the sticks in the yard

that I throw

and the brown leaves

melting under them.

Underneath everything

there is silence

as underneath the soil

the worms are always there

providing air.

© Linda Benninghoff

The Rate of Disappearance

by Hadley Hury

Hadley lives with his wife in Louisville, Kentucky, in the Beargrass Creek watershed of the Ohio River Valley.

Reading a magazine excerpt this morning

from a new study published not by some crackpot theorist

but by a prestigious scientific journal,

I learn that New York, Boston,

Miami, and all of Holland are certainly doomed.

Since we are not taking our role in global warming

seriously enough, the oceans are likely to rise

nine inches within sixty years,

more than a foot within a hundred,

and before the next two thousand years

of what we have come to call The Common Era

have elapsed, we’re looking at eight feet.

The new, more frequent, more violent hurricanes are one thing,

but it’s hard to imagine that any system of walls,

landfills, or pumps can hold back an entire ocean, and so

I wonder if some freshman class on one of Harvard’s higher hills

may survey the broad estuary the Charles has become and laugh

that they, at least, have dodged the bullet;

or whether a father can explain to his child horizonless color

from the desiccated remains of tulip bulbs

they find stuck to the rafters of a ruined barn;

or if perhaps lovers on houseboats will be listening

in the fetid twilight to some vestigial rumba or merengue

as they drift in houseboats over what used to be South Beach

or if mothers pushing strollers on the Brooklyn Heights Promenade

may look west to a shriveling Manhattan and make some silent peace

with the rate of disappearance.

I can see myself at their age, careening along

in a subway, scarcely looking at the book in my lap

but re-seeing a scene in a play or a face across a bar,

or turning a corner on the Upper West Side

smack into a bitter midnight wind,

bending toward some future.

I watch until

the tunnels and canyons fill

with an alien liquid gray,

and I then I turn the page.

© Hadley Hury

Yangshuo, China: Watching a Fisherman's Cormorant on the Li River

by Dave Evans

Dave lives a few blocks from the Sioux River in the Upper Sioux River Watershed of South Dakota. The river flows into the Missouri near his hometown, Sioux City, Iowa, about 75 miles south.

I know what it feels like: down there under

the bobbing boat is something you

need, in the shape of a fish

but every time

you

dive and come

up with one in your mouth

you discover—with a ring around

your sleek neck—it’s not yours to swallow.

© Dave Evans