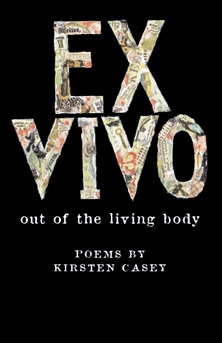

by Kirsten Casey

Publication Date: April 1, 2012

Available for $15.00 from your local bookstore or

www.amazon.com

Reviews

“Ex Vivo is a crazy quilt of a poetry book. What could unify such a varied collection of narrators—inebriated monks, famous painters, suicides, bad girls, and a woman who feels no pain? What could stitch together subjects as disparate as organ donors, middle names, anonymous corpses, keyholes, the “suspicious grieving,” pocket knives, and trees? In this collection, the binding thread is language itself, which functions not only as an instrument of communication, but as character, as place, as metaphor, as architecture, as song.”

– Cheryl Dumesnil, author of In Praise of Falling, winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize

“Kirsten Casey’s lovely Ex Vivo (Out of the Living Body) escorts us across liminal space physical and ethereal, emotional and literary. Moving deftly from the heart-out-of-the-body to the “bone of the poem” and back, she considers human motive through the lenses of persona, confession, biography, and narrative. She risks connecting: “It is not injury that I crave, but contact…,” admits its consequences: “Maybe today I am just sad without reason…,” and returns again and again to an informed optimism, from the title“Love Writes a Letter” to the last line of “A Question that You Should Say Yes To:” “I can’t even think/of the letters that spell/no when I hear your voice.””

– Molly Fisk, author of The More Difficult Beauty

“This lovely collection of poems details contemporary life, from the physical to the emotional, with tenderness, humor, and a rich understanding of our human condition. Casey’s strong poetic craft pairs with down-to-earth, flesh and bones subject matter to create poems that unfold beautifully. A wonderfully refreshing collection that will reconnect readers not only with the vividness of everyday experiences but also with the art of poetry.”

– Judy Halebsky, author of sky=empty, winner of the New Issues Poetry Prize

Ex Vivo

(outside the living body; denoting removal of an organ for reparative

surgery, after which it is returned to the original site.)

Our words uncoil like 28 feet of intestines,

specific and glistening on a stainless steel stretcher,

inside out, but still doing their job.

This angled and loopy tangle, in the dialect of the body,

is what we keep hidden in patterns, and what we

allow to leak out, warm and streaming.

We may be gutted, but we are still connected,

pulsing. And somehow, we are both the surgeon

and the patient. What we need to fix

is taken out under the brightest lights,

examined and rearranged under the limits

of time. We can only last so long outside

of ourselves, completely opened, vulnerable

to what might infect us the deepest,

to what might be too damaged, irreparable.

Every word is a vital organ.

What needs to be said cannot be replaced

by other things that need to be said.

But what comes out of the living body

can be returned to it. All of our parts

are desperate to revisit their proper place

in the order of things, to belong again

to where they came from.

This homecoming of words, this quiet return

to sequence and sentence, requires the scalpel’s red seam,

a blood ringed opening, hours of tedious mending,

and the artistry of stitching pieces together again.

What keeps us alive is a potential for reorder,

this reinvention of everything inside of us.

Doctor and poet, go ahead,

what we take out, we are allowed

to put back in again.

My four favorite bones

Femur is first, for the sound

itself—for its solid line and thick

whiteness, an inner crutch, a length,

a height.

The first vertebrae, like a precious ivory clasp,

linking latch, connecting and supporting,

a spinal handshake, upright

and forward, the captain

of the cord, steady and about to salute.

Every phalange, delicacy and downfall,

thin, pale twigs, covered in knots,

allow me to grip and drop, gather

the persimmons, address the last note, doodle

a star, mysterious under a glove of skin, talking

through cracked knuckles.

Isn’t the skull the biggest? Its dome

of glory, a living helmet, a suitcase

for a string of words, folded

and packed into soft tissue

that pulses—like dying stars, the flickers

that command—get up and walk, you

have an itch, blink now. There is a sound

inside—from the beat of blood and the buzz

of synapses—that is the bone

of the poem.

The right way to say goodbye

She leaves the motor running

not intending to end her own life,

but if she has to die to kill him,

so be it.

She leaves the motor running

not to warm the engine or fight frost,

not to hear its starting clicks, like fast spikes

in a footrace, the sound of a loud sprint

on pavement.

She leaves the motor running,

swings open the side door, and she is ajar.

Her ankles give way. She stretches out

on concrete, posed like a 40’s movie siren

on a lake rock, delicate and still

in her modest bathing suit.

She leaves the motor running

breathing exhausted, useless air.

In the fumes she sees the shapes

of every letter that spelled his hard words,

each one outlined and weighted—the color

of smoke from burning tires.

She leaves the motor running,

while he sleeps across the vinyl bench seat,

the place he crawled from the bar curb.

He tried to hit her while she drove,

and his drunk aim left her hunched, flinching.

She leaves the motor running,

staying for the finality of it.

She waits a moment too long, a second

the length of a kiss.

How many times had they slept

in the same room after a fight?

She, in a heap on the floor

like an overcoat that missed the hook.

He, unwound, heavy limbs outstretched

in solid sleep—the kind that comes

fast and dark to those who don’t know

how to forgive or regret.